Corsica's 253 year struggle for self-rule

This year's prison attack on the Corsican nationalist Yvan Colonna reignited the discussion about Corsica's struggle for nationhood from France. Colonna, who died a few weeks after the attack, was found guilty of the 1998 assassination of Claude Erignac, a representative of the French state in Corsica. For many on the island, however, he was an important figure in the region's nationalist cause.

The attack and the subsequent protests that took place are part of the 253-year history of the Corsican struggle towards recognition of their culture and language. In order to understand this struggle one has to start with the history of the island itself.

In 1755, following hundreds of years under the rule of the Republic of Genoa, Corsican hero Pascuale Paoli declared the birth of the Corsican Republic – an independent country with its own Constitution, a democratically-elected assembly, and its own currency. The Corsican Republic remained largely unrecognised by most of the existing states at the time because the Republic of Genoa still claimed the island as its own.

The declining Mediterranean superpower, however, was not capable of putting down the Corsican uprising of Paoli, and when the de facto Republic of Corsica won over the small island of Capraia from the Genoese, the latter had had enough. The Treaty of Versailles was signed with the Kingdom of France, settling a debt with the French by transferring ownership of the Corsican island to the French monarchy.

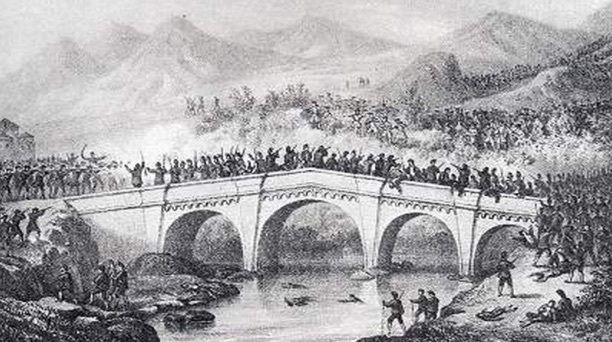

Paoli and the Corsicans did not take this well of course, and just as they had been doing against the Genoese, the Corsicans tried to fight off the French, with some early success. By 1769, the French managed to subdue the new republic at the battle of Ponte Novu and by 1770, the island became a province of the Kingdom of France.

This brief 14-year period remained engraved in the minds of Corsicans ever since, and the relationship between France and Corsica remains rocky to this day. While the French firmly believe that there can only be a unitary French state, with a single people and language, the majority of Corsicans believe that they are a nation of their own and prefer more control on local issues such as education and the local economy. There have been several efforts to achieve nationhood, some people choose violence, while others choose a more democratic route.

Since World War II, different French governments made various changes to how Corsica is administered. In 1964, Corsica was attached to the newly-created region of Provence–Côte d’Azur–Corse, only to be declared a separate region with two different departments – Haute Corse and Corse-du-Sud, in 1974. These administrative changes by the French government were aimed at addressing the economic challenges on the island, the number one grievance for Corsican nationalists, but the results proved to be limited. It was during this period, the 1970s, that a Corsican nationalist movement started to assert itself, calling for political change in the form of self-rule and protection of the island's culture and language, among a long list of grievances.

Language is one of the few things that unites Corsicans, and even then, due to the mountainous terrain of the island which made contact between different towns difficult, Corsican itself has various dialects. The language issue has been under pressure due to French nation-building, and sometimes put aside by Corsicans themselves as they move to the mainland in search of economic opportunities. At the end of the 20th century, only one of every ten children spoke Corsican with their parents, and in a recent visit to the island I only heard a couple of older people speaking the language, while most spoke in French.

Another priority high on every nationalist agenda, is the issue of clientelism that exists in Corsica, with political power divided between 'clans' or groups, supposedly left- and right-wing, centred around important families. These clans act as mediators between “the Corsican society and the state”, and are able to use the economic resources of the state to placate their relatives and friends. Nationalists fear that these clans are an obstacle to autonomy or independence, as the status quo allows them political and economic power.

In 1982, a newly elected Socialist Government in France instituted a number of reforms looking to decentralise power. This included a 'special statute' for Corsica which gave local authorities autonomy in the economic development of the island, as well as in education, culture, and social policy. In the following years, successive French governments continued to allow Corsica more control over certain issues. Despite this, it was during this time that a particular intense period of violence hit the island, mostly by the pro-independence paramilitary outfit, the National Liberation Front of Corsica (FLNC).

The FLNC, which 'launched' itself with a series of bombings on the night of 4 May 1976, waged a guerrilla campaign against the French state for over 40 years. The Front, which is the most violent of the pro-independence movements in Corsica, has conducted hundreds, if not thousands, of bombings on French targets on the island, as well as in France. It claimed to be waging a war against French "internal colonialism".

Left: French village names on road signs are commonly sprayed over by FLNC supporters. Right: IFF (I francesi fora/French out) sprayed on a wall in Bastia, Corsica

In the 1980s and 1990s, the FLNC suffered a series of internal feuds and rivalries and split the group into several offshoots, with the largest being the FLNC-Canal Historique (Historical Faction) and the FLNC-Canal Habituel (Usual Faction). This was also a time when violence increased exponentially on the island, with attacks being targeted not just on buildings but also on people that the Front deemed to be 'collaborating' with the French. This culminated in the 1998 shooting of the Prefect of Corsica, and the representative of the French government on the island, Claude Erignac. At the time, the FLNC denied responsibility for the assassination of Erignac, due to the large public outcry against this murder.

In 2003, two days before a regional referendum that sought to unite Corsica into a single stand-alone department within France, the police arrested Yvan Colonna for the assassination of Erignac, who was later sentenced to life in prison. The referendum failed to pass, with supporters of autonomy and pro-independence groups saying that the measures proposed did not go far enough.

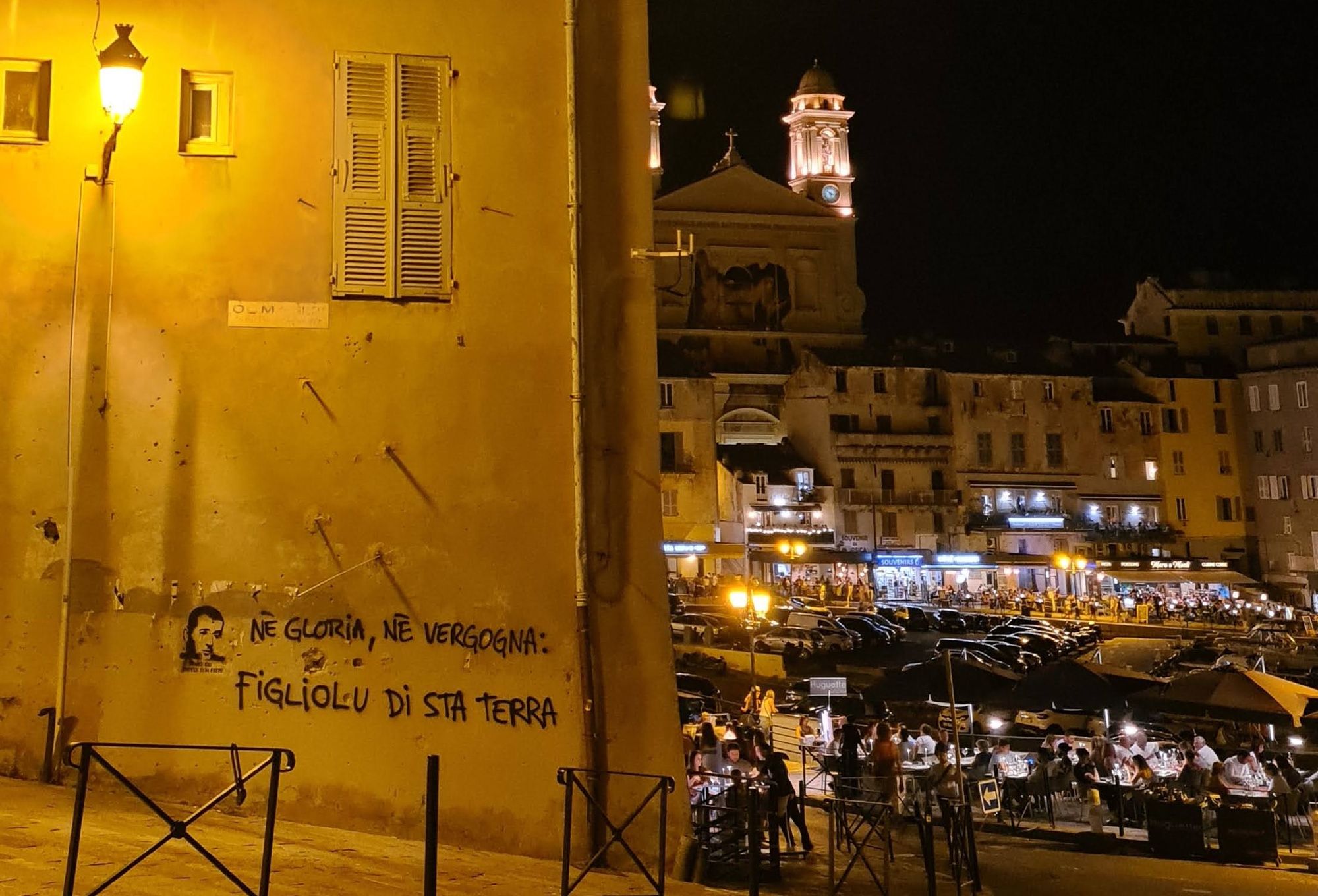

While most Corsicans did not agree with the extremist FLNC and its offshoots, a certain level of distrust in the authorities, as well as elements of omertà, led locals to turn a blind eye to violence, bank robberies, and the extortion methods used by the group to fund itself. At the same time, one can still see pro-FLNC and pro-independence graffiti all over the island, some of them newly sprayed. One can also observe a concentration of these graffiti in Bastia, Corsica's second-largest city, and in the nearby towns.

Several pro-FLNC and pro-independence graffiti can be seen in the heart of Bastia, Corsica. On the left, a Molotov cocktail is inscribed with the words "breath of freedom"

Some Corsicans chose a more democratic path towards advocating autonomy, or even independence, and over the past 10 years they have been relatively successful. Since the 2015 French regional elections, autonomist and pro-independence political parties in Corsica have controlled the majority of the seats in the Corsican Assembly. This, together with the 2014 announcement by the FLNC that the group will be ending their violent campaign, was a significant moment for Corsica itself and for democracy. The result of the 2015 elections, was re-confirmed in the 2017 Corsican territorial elections and again in the 2021 French regional elections.

These election wins bolstered the message of the autonomist parties, and the French government could no longer ignore their requests. After the 2017 territorial elections, the first Macron government had made it clear that while independence for Corsica was not on the cards, dialogue between the two partners was "imperative".

On 2 March 2022, the stabbing of Yvan Colonna by an Islamic fundamentalist in prison, led to large, sometimes violent, protests all over the island. Cars were set on fire and windows smashed in the major Corsican cities, while the courthouse in Ajaccio, was attacked by demonstrators. Thousands of Corsicans took part in the protests and more than a 100 individuals, including police officers, were injured in the resulting violence. Even the FLNC reacted to the protests, saying that “if the French state stays deaf... then the street fights of today will quickly spread to the hills at night”.

The protests, taking place during the 2022 presidential election campaign, turned the already volatile situation into a critical one. As a result, the French Interior Minister promised possible 'autonomy' for Corsica, if the protests did not escalate further. This represented a significant step and a win for the autonomist camp, because the French Government has always rejected the idea that a part of France becomes autonomist. Despite this, Interior Minister Darmanin still emphasized that "Corsica's future is fully within the French republic”.

The news was welcomed by various political parties on the island, including the leading political party in the Corsican regional government - Femu a Corsica. Many, however, will be awaiting concrete action by the French government, before dreaming of an autonomist Corsica. At the time of writing there is little evidence that things will change with regard to the status of the island.

The French government knows that giving Corsica more autonomy, will not be without consequences. The regional council in Brittany has already overwhelming voted to approach the central government with the same ask for its region. The French government also does not want to give the impression that political violence can get quick results. In an interview with the New York Times just before a huge electoral win in 2017, Gilles Simeoni, the leader of Femu a Corsica, said "half-jokingly" that "people are saying, ‘At least when we had bombs, they listened to us’".

France is now walking on a tight rope - will it go back on its commitment on autonomy and risk escalating the situation, or will it adhere to its promise and risk the future of the French nation?